When the rate of change outside of a health insurer exceeds the rate of change inside it, sound strategic vision and timely tactical action is paramount. And, today, the marketplace of health insurers and health insurance plans is undergoing disruptive change in which the future cannot be adequately understood as a simple extrapolation of the past. Consider what lies ahead:

Competition.

No longer will most cities and states be captive to a select few health insurers. In only two short years from now when the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) in the United States is implemented, the introduction of health insurance exchanges will dramatically change the landscape by expanding insurer competition.

Choice.

As a corollary, consumers' role in the choice of their health insurers and health insurance plan will expand. In 2014, 12 million consumers are anticipated to choose their own health insurers through a health insurance exchange, representing about $60 billion in premiums. Five years later, in 2019, those estimates are projected to rise to 28 million and $200 billion, respectively.1

Commoditization.

Coupled with increased transparency and enhanced ease of comparison shopping, health insurers will face greater challenges in achieving, communicating, and competing on the basis of product differentiation.

Overcoming the obstacles of increased competition, choice, and commoditization will not be easy. However, Peppers & Rogers Group's "2012 Customer Trust in Healthcare" study makes the case that the best path forward will be one that focuses on understanding and enhancing consumers' trust. A health insurer that strategically seeks to grow that trust can overcome the obstacle of competition, by setting itself apart from other health insurers on a dimension that is essential to consumers; the obstacle of choice, by narrowing the competitive set under consideration when the consumer is faced with numerous options; and the obstacle of commoditization, by elevating the decision-making process beyond product and price.

The journey to overcoming these obstacles begins with understanding the current state of consumers' trust in their health insurers, the association of trust with business outcomes, and experiential factors that enhance (or diminish) that trust. Peppers & Rogers Group's "2012 Customer Trust in Healthcare" study gathered data from 2,994 adults representing a diverse mix of ages and incomes in the United States through an online questionnaire during November 2011 to provide insight into those three areas.

Trust among health insurers

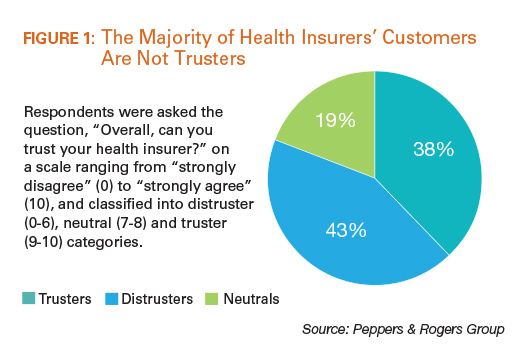

To examine trust among health insurers, respondents were classified into "distruster," "neutral," and "truster" categories (see Figure 1). Across all health insurers, a minority of respondents—only about two out of five—strongly agreed that their health insurer can be trusted on an absolute basis. "For a health insurer, this represents a challenge," says Marc Ruggiano, a partner with Peppers & Rogers Group. "In situations like health insurance, where objective complexity is high and subjective feelings of vulnerability are also high, the importance of trust is magnified."

Relative to the company in any industry that they trust the most, 71 percent of trusters also rate the trustworthiness of their own health insurer as equally (or almost as equally) trustworthy. In contrast, only 3 percent of distrusters perceive their health insurer to be nearly as trustworthy as their most trusted company. As a consequence, the bar is high: It's not sufficient for health insurers to be merely as trustworthy as their direct competition, because consumers make comparative judgments holistically and across sectors. For this reason, a health insurer's competitive set in the realm of trustworthiness includes highly trusted companies as diverse as USAA, Amazon.com, and Costco.2

Distrusters of health insurers are not distrusters of the entire healthcare sector. As compared to their health insurer's trustworthiness, the extent to which distrusters trust their primary physician to do what is best for them is 46 percent higher and, for their pharmacist, it is 43 percent higher. Thus, distrusters are not simply malcontents—they distinctly distrust their health insurer. In contrast, this pattern of results is not present for trusters, who perceive their health insurer slightly more favorably than their primary physician (2 percent) and their pharmacist (4 percent).

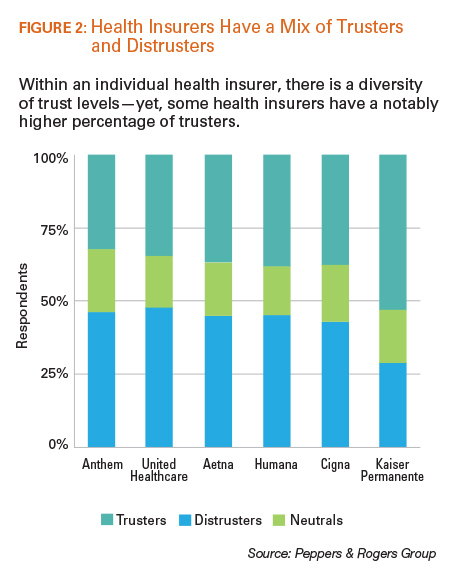

As compared to one another, the concentration of trusters across health insurers varies from a low of 33 percent to a high of 54 percent (see Figure 2). In all cases examined in this research, however, each health insurer has substantial room for improvement in developing trust more extensively across its entire consumer base, with the percentage of distrusters ranging from 29 percent to 46 percent. "This should be worrisome," notes Ruggiano, "since each health insurer has a substantial subset of consumers who don't perceive them as highly trustworthy."

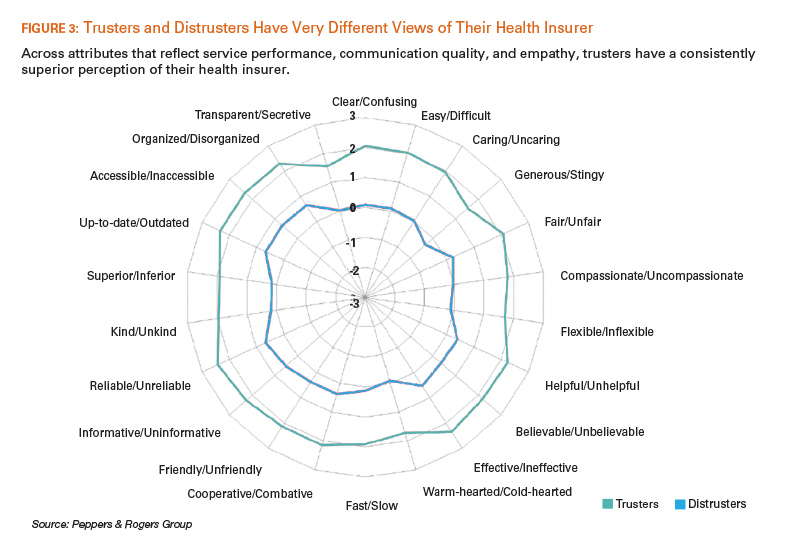

Those differences in trust are associated with very discrepant perceptions of the health insurer. Across many pairs of attributes (see Figure 3), trusters rate their health insurer much more positively than distrusters. From a service performance perspective, trusters see their health insurer as more "easy," "flexible," "helpful," "effective," "fast," "cooperative," "reliable," "superior," "up-to-date," "accessible," and "organized." From a communications perspective, trusters see their health insurer as more "clear," "believable," "informative," and "transparent." And, from an empathetic perspective, trusters see their health insurer as more "caring," "generous," "fair," "compassionate," "warm-hearted," "friendly," and "kind." In contrast, distrusters generally perceive their health insurer with indifference on most of these attributes, with mean ratings near the midpoint of the scale. These differences in perception between trusters and distrusters are reflected in important business outcomes.

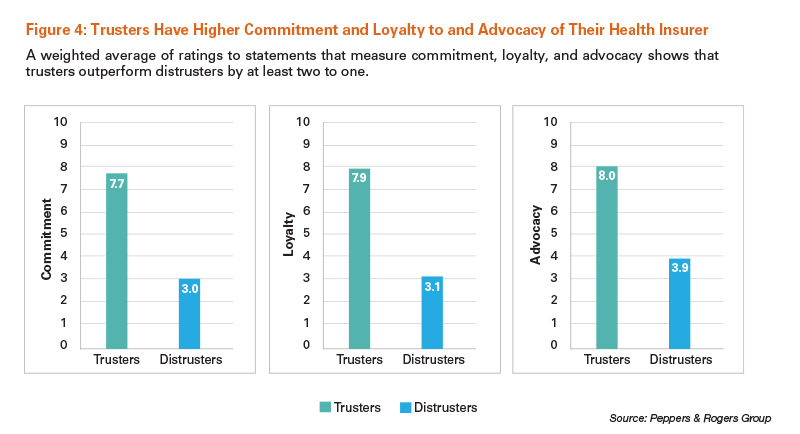

The consequences of trust

Trust is not without practical consequences (see Figure 4). The subset of consumers for a health insurer who are trusters have elevated levels of emotional commitment to the company, as measured by heightened agreement with statements such as "I feel a strong attachment to my health insurer" and "My relationship with my health insurer is very important to me." As compared to distrusters, trusters also report higher levels of loyalty and more strongly agree with statements such as "I feel a strong sense of loyalty to my health insurer" and "I anticipate that I will remain a customer of my health insurer for a long time." And, trusters are more willing to recommend their health insurer to a friend or colleague and to serve as an ambassador on behalf of the company. In all three cases, trusters outperform distrusters by a factor of two or more. "The impact of trust on the future success of health insurers is significant," says Ruggiano, "and it cannot be ignored."

Trust also impacts willingness to recommend in an employment setting, with 74 percent of trusters versus 5 percent of distrusters strongly (or nearly strongly) agreeing with the statement, "I would recommend to my employer that we keep the same health insurer next year."

Additionally, loyalty manifests itself in the context of health insurance exchanges. When asked, "If you had the opportunity to participate in a healthcare insurance exchange and your current health insurer and several others were available in the exchange, how likely would you be to select your current health insurer?" trusters were eight times more likely than distrusters to definitely (or almost definitely) select their current health insurer—47 percent versus 6 percent, respectively. "With the forthcoming introduction of health exchanges and the increased competition that will ensue, this finding is especially noteworthy," Ruggiano says.

Finally, respondents place value on trust and are willing to pay higher premiums for a health insurer that consistently demonstrates a high level of trustability as compared to one that does not, given that both offer the same levels of coverage, the same claims processing and handling, and the same networks of physicians. That price premium for trust is $29 per month on average, with 18 percent of respondents reporting a willingness to pay $51 or more per month to a trusted provider. "Trust lowers consumers' sensitivity to price," notes Ruggiano, "and together with increases in commitment, loyalty, and advocacy builds the business case for building trust."

Building trust

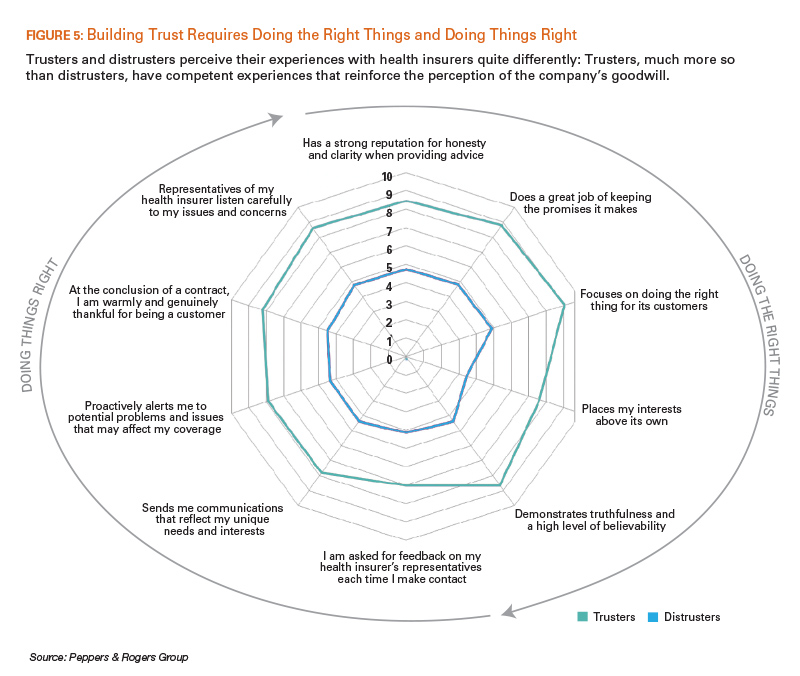

Trusters and distrusters have distinctly different perceptions of their experiences with health insurers (see Figure 5). Trusters see their health insurer doing the right things and doing things right, the two components that together drive the development of a trusted relationship. The former, reflecting the company's intent or goodwill, is shown by trusters' higher ratings of agreement to statements about their health insurer such as "focuses on doing the right thing for its customers" and "has a strong reputation for honesty and clarity when providing advice." Trusters infer that goodwill through communications and behavior, and those inferences are experientially confirmed (or disconfirmed) by the company's competence in doing things right, reported as higher levels of agreement to statements such as "I am warmly and genuinely thanked for being a customer" and "proactively alerts me to potential problems and issues that may affect my coverage."

More generally, this research has identified several practical priorities that, if implemented, will serve to enhance consumers' trust. For example, communications initiated by the health insurer should be clear, using easily understood language, and delivered on a timely basis. When contacted by a consumer, health insurers' interactions should exhibit competence in problem solving, conveying that the individual is being listened to carefully, asking for feedback, and offering an apology when a mistake has been made. Delivering well on the foundational basics is important for building trust, too: making plan enrollment easy and straightforward, working well with doctors' offices, processing claims accurately, and having innovative and beneficial technology. "Health insurers that successfully alter their own behavior in these ways," explains Ruggiano, "will also succeed in reaping the benefits of altered consumer behaviors: improved retention, referral, and advocacy."

Moving forward

A health insurer can know the extent to which it has earned the trust of its consumers—it is not a philosophical mystery, but a practical metric. And, a health insurer should know, because it provides a direction for growth in these times that are about to become more tumultuous. And, finally, a health insurer must know, because continued business success is contingent upon it.

For forward-thinking health insurers, trust will serve as a beacon to guide strategic priorities, to align compensation and incentive plans, and to prioritize tactical efforts into a high-impact roadmap that delivers "early wins" and lays the foundation for the future. Get ready.

Footnotes

1. Change the Channel: Health Insurance Exchanges Expand Choice and Competition. Retrieved January 27, 2012, from: http://www.pwc.com

2. 2011 Temkin Trust Ratings. Retrieved February 1, 2012, from: http://www.temkinratings.com